“Liberation work isn’t easy. Detoxification requires painful withdrawals. Only those committed to overcoming toxicity can enjoy sobriety.”

Introduction: The Dangerous Appeal of Convenience

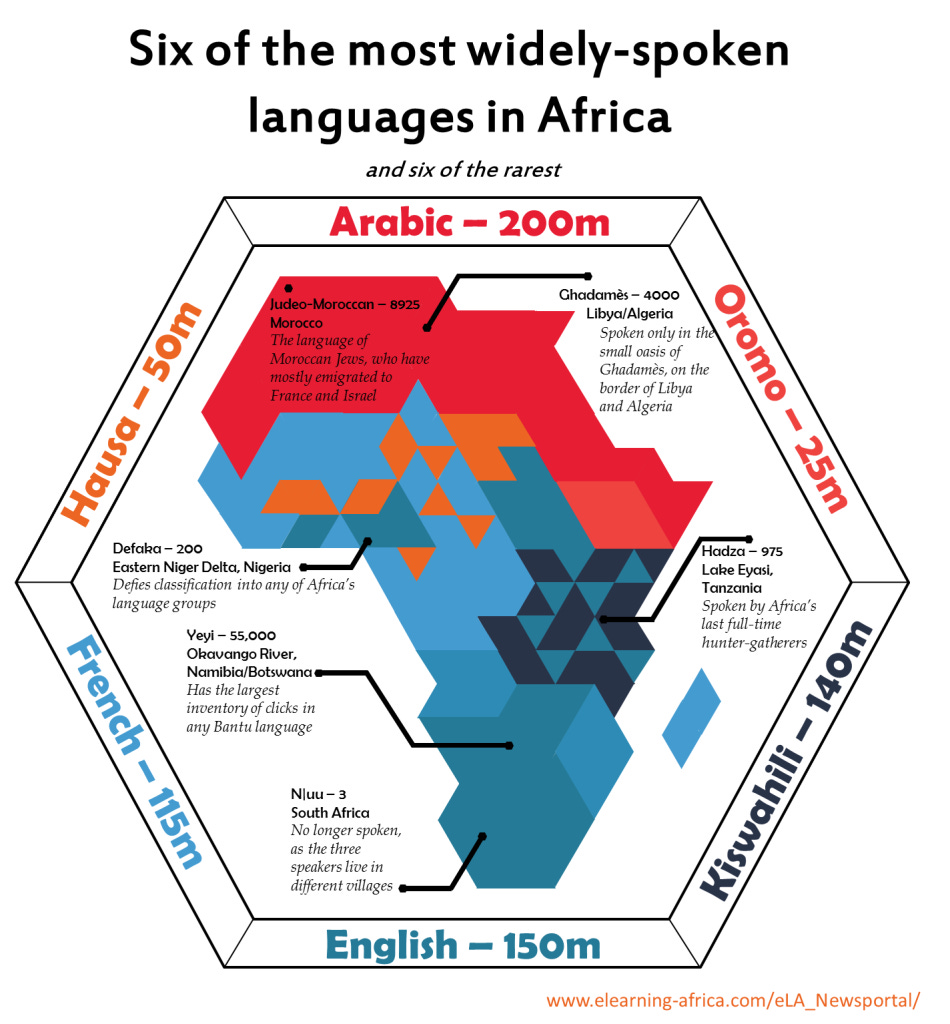

In many discussions I’ve had and I’ve heard, Pan-Africanists are talking about the need for One African Language. And within that context, there is very little debate on what that language should be:

“Let’s make Swahili the official language of Africa!”

It sounds unifying. It feels Pan-African. It seems easy.

After all, Swahili is widely spoken. It has critical mass. Arabic, English and French certainly should not count. Right?

But Pan-Africanism isn’t about convenience. It’s about sovereignty.

What Is Sovereignty?

“Sovereignty is not just what God has. Sovereignty is who God is. And we were made in His likeness.”

✅ Sovereignty means rejecting systems shaped by foreign domination.

✅ It means reclaiming what is ours—not what was given to us by those who exploited us.

🗝️Liberation Work Isn’t Easy

Real decolonization isn’t about choosing what’s simple.

✅ It is the hard work of detoxification.

✅ It means confronting painful truths about our dependency.

✅ It requires rejecting anything that continues to bind us to external control.

“Adopting Swahili is simply because it’s easy. It’ll take less effort to get people on board. But liberation work isn’t easy. Detoxification requires painful withdrawals. Only those committed to overcoming toxicity can enjoy sobriety.”

🚫Swahili: A Language Compromised by Empire

Swahili is, linguistically, a Bantu language. It is African in its grammatical core.

But that’s not the whole story.

1️⃣Arab Imperial Imprint

Swahili developed as a trade language along the East African coast.

It was shaped by centuries of Arab merchant activity, including the brutal East African slave trade.

Its vocabulary contains 15–30% Arabic loanwords.

Arab influence wasn’t cultural exchange between equals—it was often domination and extraction.

✅ Adopting Swahili as a continental language risks legitimizing a history of Arab imperialism on African shores.

2️⃣No Indigenous African Writing System

Swahili never developed its own precolonial African script.

Historically, it was written in Arabic script (Ajami)—an imported system.

In modern times, it uses Latin script, the mark of European colonialism.

✅ Swahili’s written tradition is dependent on foreign scripts.

✅ It does not represent African ownership of the means of literacy.

3️⃣Colonial Tool of Administration

European colonizers deliberately promoted Swahili as a lingua franca.

They standardized it for easier governance.

They chose it precisely because it was already hybrid enough to be controllable—neither too local nor too threatening.

✅ Swahili was an administrative convenience for colonizers—not a language of African liberation.

⚖️The Danger of Creating a New Supremacist Class

There’s another reason Swahili is so tempting:

It already has millions of speakers. It seems like an easy “shortcut” to unity.

But unity built on unequal power is not unity.

✅ Those with existing fluency in Swahili would gain immediate social, economic, and political advantage.

✅ They would become a new gatekeeping class—able to control communication, government, commerce, education.

✅ This reproduces the very logic of supremacy that we need to reject in order to heal from White domination.

European empires were built on a philosophy of scarcity:

Scarcity requires hierarchy.

Hierarchy requires domination.

Domination requires control of language.

If Africa adopts Swahili wholesale, it risks choosing ease over equity—and creating new internal supremacies.

✅ True sovereignty requires rejecting this scarcity mindset.

✅ It means choosing a language project that demands shared work, shared sacrifice, and shared ownership.

✅

A Higher Standard: True Linguistic Sovereignty

If Africa is serious about unity and liberation, it must ask:

Does this language truly belong to us? Or is it a tool we learned from someone else?

✅ Sovereignty means owning the means of communication in all its forms.

✅ That necessitates indigenous writing systems, developed independently on African soil.

Why?

Writing systems are cultural property.

They encode our philosophy, spirituality, history, and identity.

They prove our capacity to think and record in our own terms.

🌟Indigenous African Scripts: Proof of True Sovereignty

If we want an African language that embodies sovereign literacy, it must have:

✅ An indigenous precolonial writing system.

✅ A lineage that is fully ours—not borrowed.

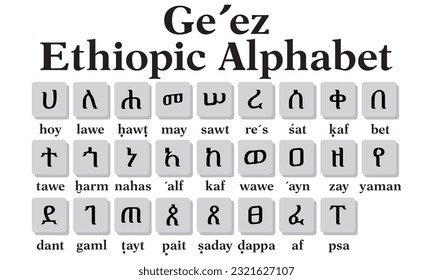

✅Geʽez (and its descendants Amharic, Tigrinya)

Written in the Geʽez script, an ancient, indigenous African writing system.

Contrary to colonial myths, Geʽez did not derive from Sabaean.

Aksum was the mother civilization, with Sheba as Ethiopian—not the student of Arabia but the teacher.

South Arabian scripts emerged through contact with Aksumite Africa, not the other way around.

Geʽez remains the sacred language of Tewahedo Christianity.

It is no people’s common tongue. It is a learned language—even Ethiopians study it deliberately.

And to those who say, “Ge'ez would advantage the Ethiopians and Eritreans!” Know this: the priests of the church use ge’ez in the same way as parents use pig Latin to around the children! 😂

✅ Choosing Geʽez wouldn’t hand any region easy supremacy.

✅ It demands shared work, shared humility, and shared ownership.

✅ Geʽez is sovereign African intellectual property.

✅Tamazight / Berber Languages

Written in Tifinagh, an indigenous alphabet with ancient roots in North Africa.

Tifinagh descends from Libyco-Berber script, predating Greco-Roman or Arab cultural domination.

Tamazight resists both Arabization and European erasure.

It stands as proof of Africa’s own capacity for literacy north of the Sahara.

✅ Tamazight represents a continental heritage of resistance.

✅Nsibidi (Nigeria/Cameroon)

An indigenous West African ideographic system.

Used for laws, social contracts, proverbs, and sacred societies.

Preserved its sovereignty even under colonial repression.

✅ Nsibidi challenges colonial literacy bias by affirming African symbolic knowledge.

✅

Meroitic (Ancient Kush, Sudan)

The script of the ancient Kingdom of Kush.

Monumental inscriptions prove state-level African literacy before foreign conquest.

Though partly undeciphered, it remains African cultural property. Yet, this reality makes it an unlikely candidate.

✅ Meroitic is an ancestral claim to African civilization.

🗺️A Vision for Linguistic Sovereignty

Imagine an Africa that:

Refuses colonial scripts as the only path to literacy.

Teaches children African languages in African alphabets. Even “transliterating” local/regional languages in an indigenously African script rather than Latin or Arabic scripting.

Honors its own ancient writing systems as acts of cultural resistance.

“Africa for Africans” must mean Africa’s voice in Africa’s alphabet.

✊🏾Conclusion: Africa Must Choose Sovereignty Over Convenience

Swahili is easy.

But easy isn’t liberation.

✅ Liberation is hard.

✅ Liberation means detoxifying from foreign domination—even the domination we’ve come to accept as normal.

✅ Liberation means refusing to create new hierarchies by giving one region linguistic supremacy over the rest.

✅ Liberation means reclaiming the full weight of African ownership—from our spoken words to our written symbols.

Our tongues must be sovereign. Our writing must be ours. Our minds must be free. For, how can one ever be emancipated from mental slavery while using another’s language?

📣Call to Action

If you care about true African liberation:

✅ Ask the hard questions.

✅ Challenge the easy answers.

✅ Demand that our unity be built on African foundations—not colonial or Arab legacies.

✅ Share this conversation and push it further.

Liberation is not for the faint-hearted. Let us choose the path of sovereignty.

What do you choose?

---

### 📚 Further Reading

- Camps, G. 1996. *Écriture Libyco‑Berbère*.

- Nurse & Hinnebusch. 1993. *Swahili and Sabaki History*.

- Bekerie, A. 2003. “De‑colonizing Geʽez.” *Int’l Journal of Ethiopian Studies*.

- Maddy‑Weitzman, B. 2011. *The Berber Identity Movement and Tifinagh Revival*.

- *British Museum – Written in Stone: Libyco‑Berber Scripts*.

- *Princeton Africana Studies – Geʽez Script Primer*.